A longer version of a short piece for the launch issue of ROMchip: a journal of game histories. The editors asked ‘What could the history of games be?’

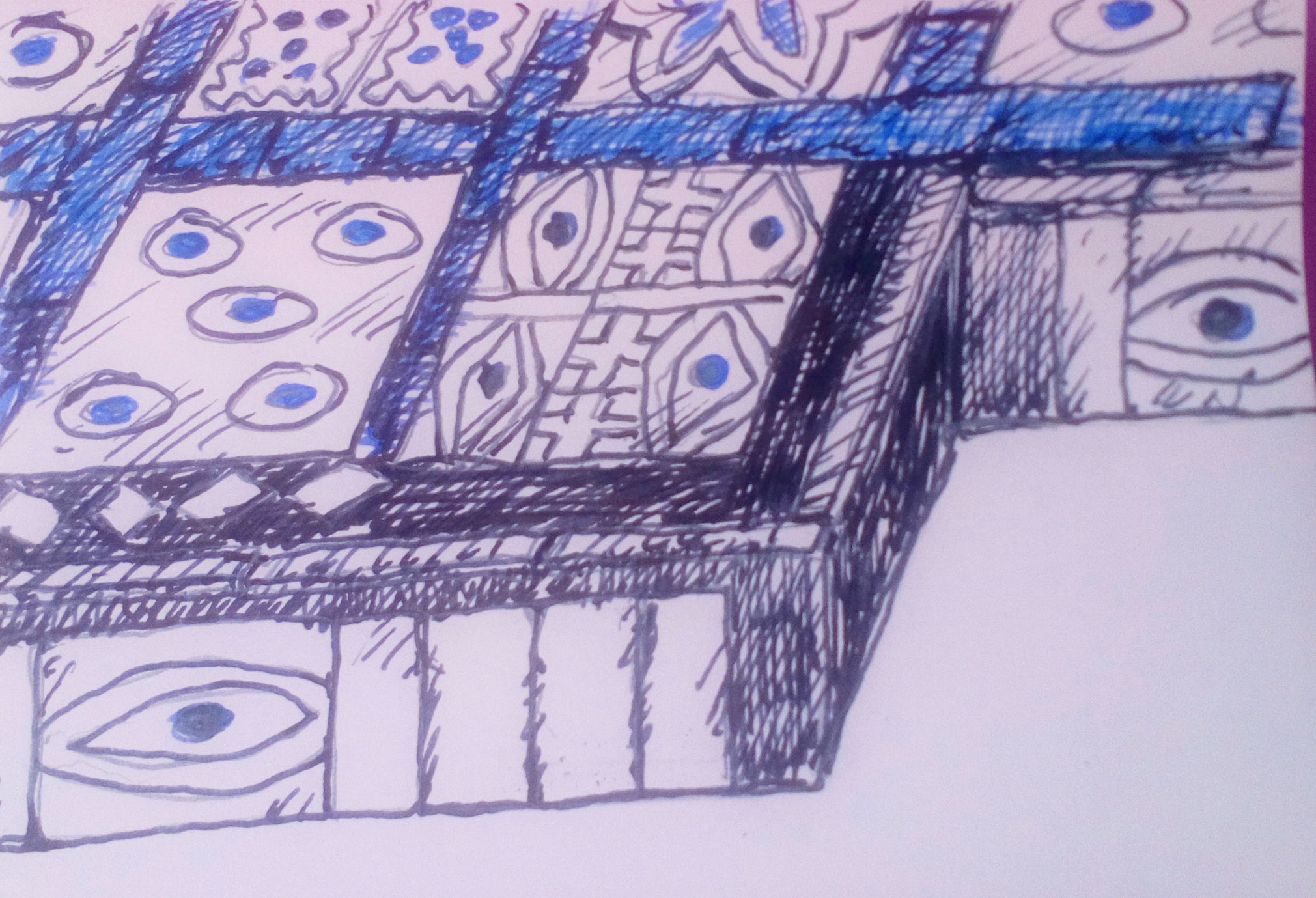

Among the British Museum’s thirteen million objects is a beautiful game board and set of counters or tokens fashioned from wood and inlaid with shells forming rosettes and eyes. The Royal Game of Ur was excavated from a royal cemetery in what is now southern Iraq and is dated to 2600–2400 BC. It demonstrates that board games are embedded deep in human history and that their key formal aspects are surprisingly persistent: after four and a half millennia this object is immediately recognizable as a board game and can still be played. Unlike other archaic art forms such as painting or epic poetry, the board game suggests a persistence and continuity of modes of reception or use, of the social behaviors and relationships that attended it and that it engendered. Its scale, formal organization of grid and tokens, and the nature and number of tokens all strongly suggest the number of players, the mode of game play, even the positioning of the players in relation to the board, and with a little more imagination perhaps the duration of particular playings, its possibilities for gambling, and so on. In this sense it is a technical object, a machine for generating and sustaining playful behavior. Its technological characteristics rather than its symbolic or communicative nature are key to its cultural significance and longevity.

All games consist of tangible and intangible techniques and technologies. Ancient games exploited the physical characteristics of animal knuckle bones and gravity for the harnessing of chance or fate, the randomizing techniques that underpin gambling from ancient Rome to contemporary casinos. Game boards from Ur to chess to Mario Party augment cognitive and imaginative processes: marking and storing the position of tokens and their algorithmic relationships, shaping and driving ludic movement, interactions, and accumulation. In this regard, board and card games and gambling games with dice or bones trouble historical and cultural periodization. For game studies the ontological emphasis in considering the relationship between non- or pre-digital games and digital games has often been on the continuity of a game-as-form regardless of platform. The game, it is asserted, consists in its rules not in its material instantiation at any particular point in history. Chess is the same game whether is played on a wooden board or in virtual space. However, if we insist instead on a critical attention to games as always-already technological then a more nuanced cultural-historical dynamic opens up.

Games are generally (though by no means always) of a scale that fits with the ergonomics and mechanics of the hand and the colocation of human bodies—dice (or bones) that are small enough to be shaken in a loosely held fist, cards that can be fanned and shuffled, boards that can be sat around. Though digital games are often (though by no means always) released from the ergonomic demands of colocated players, their interfaces and peripherals are still anthropomorphic, determined by the hand (controllers), eyes (screen), and ear (speakers, headphones). Even the rule set itself can be considered technical, a procedure or set of techniques for organizing game objects and their players in time and space. At the very least. then, material changes to ludic machines change the bodily and perceptual techniques required to play, and hence drive changes in playful behavior and sociality.

The eyes that gaze out at us from the Ur squares are clearly etched in mother-of-pearl but their symbolic import is enigmatic. They suggest that as media technologies the cultural salience of games is primarily not that of the representational. Game machines do not communicate so much as initiate and scaffold sociality and communion. It is not even necessarily the case that profound symbolic significance embedded in the eyes and rosettes has been simply clouded by millenia. Rather, as Roger Caillois suggests, games are always-already a residue of formal or official cosmology and ritual. The hopscotch grid decathected the medieval Christian supplicant’s symbolic path through the labyrinth (Caillois 2001[1958]: 82), and engineers instead a device for the choreography of a kinaesthetic and meaningless play. Though we cannot excavate the immediate experiential and social contexts of particular moments of play over millennia the very technical form of a board game strongly suggests an ephemeral, liminoid cultural context, not one of religious practice, governmentality or calendrical custom and festival. Whilst there may well have been now-forgotten connections with prevailing symbolic orders and processes, we feel that they are first and foremost games in the modern sense, their mechanical and technical nature determining a limited range of noninstrumental and insignficant behaviours. They are artefacts and evidence of a long history of trivial and interstitial sociality, a (very) long liminoid modernity.

The challenge for game history in this regard then is less that of tracking continuities and identifying changes in material and technical form, game play, and so on, and more one of recognizing and acknowledging the complex and nonlinear relationships that constitute ludic technicity over time. This would include mechanical devices, abstract rule sets, cultural and social formations and reformations, the immateriality of imagination and sociality, and the materiality of aesthetics and kinesthetics. As Hanna Wirman and Olli Tapio Leino note in their study of the traditional Chinese game Mahjong across its proliferating transmedial platforms and technologies, ‘we have learned how the various analogue, mechanical, and digital versions of Mahjong […] differ in terms of the ways in which they involve tactility, performativity, and ritualistic aspects [and] how these differences lead to affordances for significantly different kinds of play, ranging from competition-oriented skill-based gameplay to improvisational, chaotic, and joyous free-form play’ (Wirman and Leino 2017: 9). Whatever the continuities of the rule set, Wirman and Leino demonstrate, changes to the technological apparatus of a game themselves inflect or transform the nature of the game itself as an event that embodied, social, rhythmic, and spatial.

Game history then could also be game archaeology, game paleontology, game ethology. It might also address the obverse of this argument: that history of technology might not only, or even not primarily, be the history of the development of tools and instrumental technical systems, but rather one of playful and interstitial techniques—of corporeal and cognitive pleasure and sociality.

Caillois, Roger (2001 [1958]) Man, Play and Games. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Wirman, Hanna and Leino, Olli Tapio (2017) From manual to automated to digital: on transmediality, technological specificity, and playful practice in Mahjong, Games and Culture. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1555412017721840

Image drawn from: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1d/British_Museum_Royal_Game_of_Ur.jpg

One thought on “the history of games is the history of technology”