[In early critical texts (mid to late 1980s) on the cultural economy of computer games] Fiske & Watts and Bernstein make reference to Roland Barthes’ 1950s account of Japanese players of pachinko. For Barthes, pachinko – a mechanical arcade game, somewhere between pinball, bagatelle and the fruit machine – and its players are at once an allegory of, and palliative for, wage labour under advanced capitalism. The players lined up at their machines are (again) redolent of the assembly line, whilst the mechanics and playing of this game are explicable as remedial microcosm of the lived experience of restricted capitalist economies, but one that holds out the promise of, however rarely and briefly, a ‘general economy’ eruption of excess from the mechanically-regulated restricted system of coins and rewards:

the player, with an abrupt gesture… feeds the machine with his metal marbles; he stuffs them in… from time to time the machine, filled to capacity, releases its diarrhea of marbles; for a few yen, the player is symbolically spattered with money. Here we understand the seriousness of a game which counters the constipated parsimony of salaries, the constriction of capitalist wealth, with the voluptuous debacle of silver balls, which, all of a sudden, fill the player’s hand (Barthes 1982: 28).

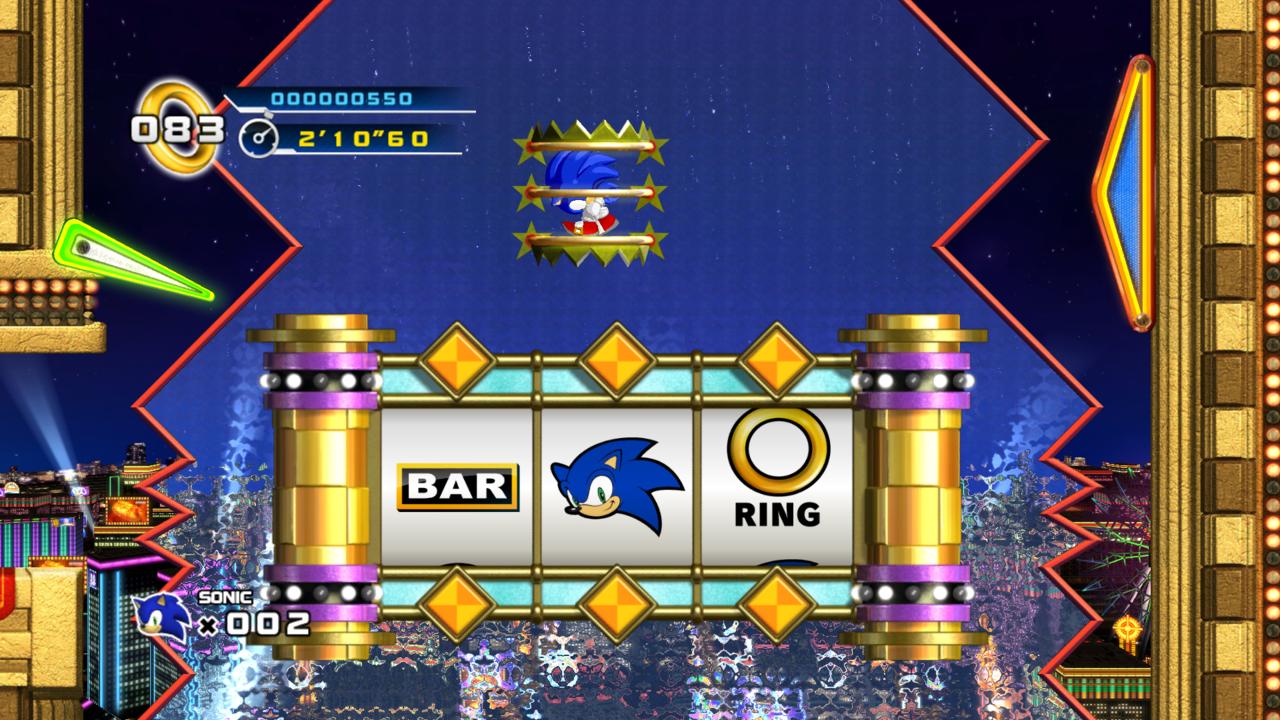

Constipation, constraint and work-like attention to the machine – but with moments of sudden voluptuous release and reward, the mechanisms of restricted and general economies are played out and through arcade machines and players’ bodies and desires. There are clear connections here with the Western fruit machine and its promise of plenty from complicated and systematised mechanisms, and this play between aleatory restriction and semiotic and experiential excess is evident in contemporary digital games, not least ‘free to play’ mobile games. Candy Crush for instance is a simulated orgy of consumption – the player sees hundreds of sweets consumed every time he or she plays. That they don’t actually eat or taste the sweets is compensated for in the visual plenitude or excess of their appearance and animated disappearance, in their vivid colours and the glistening almost tactile sheen of their surfaces and wrappers, and in the voluptuous feedback loops of generation, transformation and annihilation of virtual goods.

Like pachinko and fruit machines there is a system of equivalence and value, and a mechanical balance between random fate (the vagaries of physics in pachinko, the algorithmic distribution and alignment of tokens in fruit machines and Candy Crush), but these devices of the games’ restricted economy only make sense – only make pleasure – when nested within the general potential or trajectories of players’ bodily engagement, ludic attitudes and – perhaps – libidinal economic investment.

(adapted from ‘Accursed play: the economic imaginary of early game studies’, Games and Culture (in press)).