In Toy Theory I have plotted points at which economic systems and imaginaries are evident in toys and games, from the proto-economics of ancient board games to the microtransactions of contemporary apps – all via the distinct device of tokens as at once play objects and proto- or para-currency. I suggest, more or less playfully, that the formal and systematic characteristics of the money form are evident in the token economies of Ancient board and dice games, in funerary objects, and in more recent toy systems including the soldiers of wargaming.

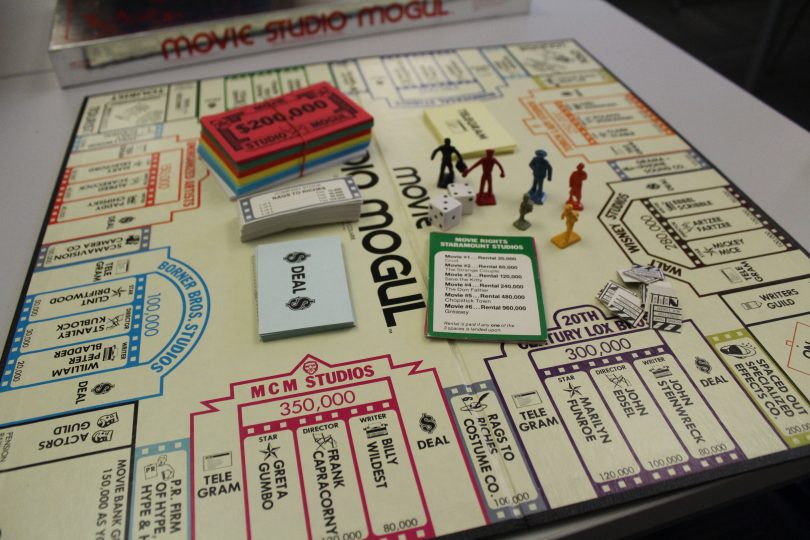

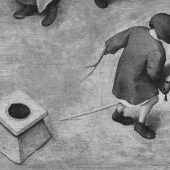

Contemporary and emergent developments in digital game-based formats within which toys and toy-like objects circulate can be fully accounted for only through the analysis of their economic dimensions as licenced IP, commercial investment in new formats and modes of distribution, and the new business models of attention, microtransaction and data-mining. On one level this is nothing new, toys were among the first consumer commodities[i] in early mercantile capitalism and have been integral to changes in materials, modes of production, and the economics of domestic life ever since. It is useful to note too that board games and card games have always been systems with economic aspects.[ii] Among the earliest games are gambling games such as knucklebones, documented in Ancient Greece and across Asia and the Middle East. Small animal bones were shaken in the hand and rolled, their arrangements and positions generating unpredictable results, a randomisation mechanic that would be re-engineered in dice for gambling and board games, and later wargames and tabletop roleplaying games, and which, in algorithmic form, still underpins key aspects of most digital games today.[iii] Whether played for money like gambling or not, most games are based in proto-economic systems of value, exchange and expenditure.

The ambiguous character of toys reaches a limit in the game. The physical objects of predigital games – counters, tokens, cards, figurines – have value only in the game-as-system, values ascribed by the rules, arbitrary in every sense except that of game mechanics and operation. In digital games, the studs that underpin LEGO as a mechanical system become both a marker of intellectual property and a currency: as ubiquitous tokens filling the world or smashed from the destruction of virtual objects, hovering in the air for a few seconds before being collected by the avatar minifig or evaporating. Contemporary toy systems need to be understood not only in their articulation of the physical and the virtual, but also the game and game-like structures through which this articulation is effected. Game tokens and their systems of value predate and prefigure actual money economies by millennia. They share significant features with money, but do not appear to connect directly with the latter’s historical emergence. These features – systems of multiplicity and formal/ludic difference do connect directly however with the toyetic dynamics of multiplicity, collection and the miniature addressed elsewhere in this book. I’ve highlighted the significance of the functioning of sets and collections in toys, from tin soldiers to dolls’ houses and Noah’s Arks to Pokémon, objects that make sense only as part of a set or series. The imperative to collect and arrange identical – or systematically varied – objects is fully exploited in children’s consumer capitalism, but predates it.[iv]

————————————

[i] In the contemporary ‘consumer society’ sense of the commodity as something more (or less) than a material need.

[ii] Seth Giddings, “Accursed Play: The Economic Imaginary of Early Game Studiesm,” Games and Culture 13, no.7 (2018), 765-783.

[iii] Recent games and toy collection systems have returned directly to the knucklebone-shape – including Jacks, Pass the Pigs (1977, still in production) and the GoGo Crazy Bones game / collection line (hugely popular around the turn of twenty-first century)

[iv] Archaeologists have found collections of non-utilitarian and non-decorative objects such as crystals back to over 100,000 years ago (New Scientist 10/4/21: 18)