edited excerpt from Ashton and Giddings 2018, At work in the toy box: bedrooms, playgrounds and theories of play in creative cultural work International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation:

The appeal of the consultancy programme LEGO Serious Play is in part generated by the tension between work and play. The name itself jams together the Serious and the Playful, and the notion of using these much-loved bricks in the offices and boardrooms of industry has a wry charm: nostalgia for lost time of childhood play and the domestic spaces of bedroom and living room floors and tables. This connection between LEGO Serious Play and everyday play with LEGO in homes and children’s bedrooms is clear and intentional. The scheme draws on LEGO’s unique status as a product loved for its creative and educational affordances and its role in family life over the generations since its development in Denmark in the 1950s (Lauwaert 2009). Because of this, Serious Play has received a level of popular attention unique for a management training development programme.

LEGO Serious Play was developed in the mid 1990s by the LEGO Group, manufacturers of the popular toys. A trained facilitator leads group building of LEGO models from a specially designed set of bricks. The aim is for groups to represent their workplace structures, roles, relationships, identities and communications metaphorically. As the media scholar David Gauntlett – himself a trained Serious Play facilitator – puts it:

a school would not be constructed as a building with doors and windows, but would be represented with interconnected metaphors such as an owl representing knowledge, flowers representing emotional support, a tower for leadership, and a staircase representing personal growth (Gauntlett, 2014, p. 193-4).

Once these intangible phenomena were ‘externalised’ in playfully metaphorical models, participants were encouraged to reflect on them, and to use the LEGO bricks to construct alternative models, suggesting new approaches and initiatives.

The popular appeal of LEGO is bound up in the perception that it is amongst the most creative and imaginative toys or games available to children. This is the heart of LEGO’s corporate image. The LEGO Group has supported research into play, and its website and publications are characterised by advanced claims for the value of open and imaginative play for children’s development. Listing its brand values as ‘Imagination, Creativity, Fun, Learning’ it has developed, in part through its connections with the LEGO Foundation, an ethos of play for learning that is promoted and pursued in global campaigns and projects (Lachney 2014). LEGO Serious Play builds on this image, research, values, and assumptions about play.

In their book on the Serious Play method in business, Kristiansen and Rasmussen draw on Johan Huizinga’s seminal volume on the history and philosophy of play, Homo Ludens, to set up a conceptual framework for Serious Play and its relationship with children’s play. They argue that children’s play can be, and often is, serious and intense. In terms fully compatible with the rhetoric of play as progress, they assert that play generally has an underlying developmental function:

We should probably make it clear that most play is anything but frivolous. Even the kinds in which we partake when we’re young typically have some sort of developmental purpose, even though this purpose typically is not explicitly stated (Kristiansen & Rasmussen, 2014, p 39. Emphasis in original).

The Serious Play method then aims to harness and direct this underlying and natural developmental potential into the work environments of corporate and entrepreneurial strategy: ‘play with an explicit purpose […] to address a real issue for participants around the table by getting them to lean forward, unlock knowledge, and break habitual thinking’ (39).

The Serious Play ethos is not a radical break from LEGO as a children’s toy, rather it could be seen as a focused application and development of a long-established corporate philosophy. On its website, company reports and in the research it supports, the LEGO Group and the LEGO Foundation set out in detail a consistent philosophy of the value of play:

Playfulness asks what if? and imagines how the ordinary becomes extraordinary, fantasy or fiction. Dreaming it is a first step towards doing it.

Free play is how children develop their imagination – the foundation for creativity.

As in Serious Play imagination and ‘dreaming’ are regarded as fundamental to productive thought, learning, and activity:

Creativity is the ability to come up with ideas and things that are new, surprising and valuable. Systematic creativity is a particular form of creativity that combines logic and reasoning with playfulness and imagination. (http://www.lego.com/en-gb/aboutus/lego-group/the_lego_brand).

Fault lines in industrial theories of play

[…] the application of play for the instrumental demands of industry, however open and forward-looking, must at least implicitly establish a distinction between play as progress and play as frivolity. Given its philosophical ambitions and close association with, and validation from, specific types and locations of children’s play (LEGO toys, the home, bedroom floors), Serious Play polices this boundary explicitly. Kristiansen and Rasmussen (2014, p. 122-23) assert that:

there is a clear division between creative imagination, where one focuses on possible realities and the making of reality, and fantasy, the domain of the impossible. When the creative imagination is taken to a negative extreme, we risk indulging in fantasy, the impossible, and the improbable. Strategy makers who lose touch with their experience risk fantasizing.

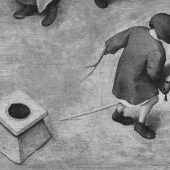

Though they don’t spell it out in these terms, here we see a distinction from the time and place of children’s play – an explanation and justification of the application of ostensibly childlike activity to serious adult work. And it returns us to questions about the extent to which the assumptions of play places and play activities – physical and mental – that underpin these business applications are founded on actual everyday play and places. For example, in ethnographic and ecological-psychological studies of children’s games, imaginative play is often observed to be characterised by nonsensical action, characters and scenarios rather than the widely-held assumption that in imaginative play children are generally trying out adult roles (pretending to be doctors or parents) (Burns and Richards, 2014; Opie, 1994; Sutton Smith, 1997). Sutton-Smith’s play as frivolity is ubiquitous and omnipotent in the play of young children – in the playground and with toys. He also describes it as phantasmagorical, a term which captures both its fantastical and whimsical manifestations but also the creative impulse that the proponents of industrial play work to isolate and apply. Children’s play with toys, their songs and jokes and their playground games are often, and perhaps more often than not, characterised by nonsense, obscenity and figurative violence, monsters and catastrophes. Children’s own stories, he notes, ‘portray a world of great flux, anarchy and disaster often without resolution’, with ‘crazy titles, morals, and characters’ (Sutton-Smith, 1997, p 161).

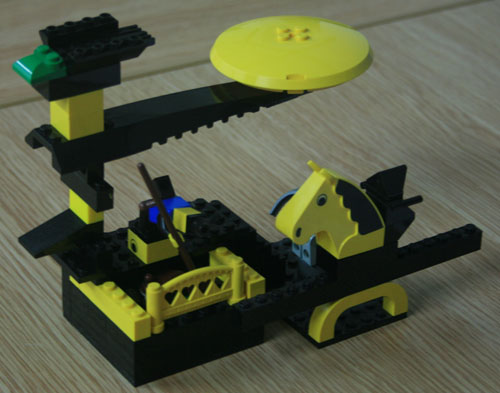

Despite its reputation for educational potential, LEGO play does not escape this phantasmagoria, indeed it appears to encourage it. The few ethnographic studies of LEGO play or construction toy play capture nonsensical worlds and events (e.g. Giddings, 2014b). For example, this short study of three boys playing with LEGO together soon after a series of riots had hit the headlines in the UK:

J: I only have two people, but they have sticks!

A & N: fighting / shooting / imact noises

N: Is my guy ever going to die?

A: No!

J: This guy dies.

A: This guy’s my last rioter…

N: No! No! Not yet! He doesn’t die yet!

N: I’ll tell you when he can die.

J: There’s a fake policeman… Alex, I killed him with his own neon riot stick.

J: You know riot shields? This is what they do…

J: Alex, I’m just beating this guy to death with his own stick!

N: The police have got a robot!

A: Err! Err! Err!

J: It’s a bomb disposal… I’ve beaten him so hard his legs fell off.

J: Grr! The last rioter alive!

(Giddings, 2014a, p 140-141).

This moment of LEGO play is clearly imaginative, responsive to real world events and concerns, but its exaggerated violence and surreal juxtapositions could not in any straightforward way be recuperable for productive, reflective, or strategic ends, that is to say it does not feature in LEGO’s promotional or training material for Serious Play. Play, these LEGO rioters suggest, is not so easily understood, nor applied – it has its own (il)logics and potentials. The links between play, creativity, and innovation are real, but they are complex and not easily tamed.