Microethology of toys-to-life (from proposal for Toy Theory book)

– I’m going to build Dumbledore [sings:] Dumbledore, Dumbledore…

– Technically, you’re building Gandalf

[They rip open the small plastic bags containing LEGO pieces and minfigs]

– [In a gruff voice] I only use black and very very very dark grey… Why am I quoting Batman? Black and dark grey, black and dark grey

– [Opens small card carton] His cape gets its own box! …cape gets its own box, it’s cape-able of doing it!

– That’s a bad joke…

– It’s a cape-astrophe! [Sings] Dumbledore! Dumbledore!

– It’s not Dumbledore…

– Dumbledore! Dumbledore! Dumbledore!

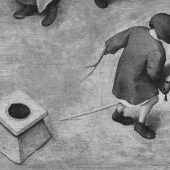

The two brothers, neighbours of mine, are sitting on the rug, setting up a LEGO Dimensions set, working with a printed book of instructions, opening bags of bricks and clicking minifigs together. The room also contains a Nintendo 3DS console and a Wii U connected to a TV screen. There are also Skylanders and Disney Infinity sets, but the research session does not allow enough time for them to be opened and played with. We have earlier experimented with Nintendo Amiibo figures, connecting them during play with Splatoon, a cartoony first person shooter game. I am video recording the play.

The promise of these hybrid toy-videogame systems, and broader developments in the ‘Internet of Toys’ (Mascheroni and Holloway 2019) is to collapse the boundaries between the virtual spaces of videogames and digital networks and the actual environment and objects of everyday play. In part they are a response to engrained assumptions that actual and virtual play spaces are distinct and separate, with the latter a threat to the former. Conceptual and ethnographic work in media studies and game studies has repeatedly demonstrated both the fluidity of play across virtual and actual spaces (Giddings 2007, 2011), and has drawn attention to the multiplicity of communicative, playful and symbolic domains that overlap in play. The event of gameplay described here takes place as much within a persistent landscape of transmedia franchises, improvised songs, quotes, and distracted references connect to the LEGO Movie, the Lord of the Rings films, the Harry Potter universe. Hybrid game systems such as LEGO Dimensions and Disney Infinity both acknowledge and exploit the tendency of children’s imaginative play to grab, mix and hybridise diverse fictional worlds and characters. The LEGO Batman films and LEGO Movie films themselves are a sustained joke about the mix and jumble of the modular toy itself, an analogue and allegory of mixed-up sets and stories in everyday bedrooms.

The boys’ father enters the room and they excitedly but distractedly explain what they are doing.

– … You actually build the videogame!

Their father asks if clicking the bricks together creates circuits.

– No, you just put it [shows a minifig] here and it works!

– Gandalf does all the magic!

– [Singsong voice] Gandalf, magic, makes it all work…

– [Rummaging in the bricks] Where’s whatshername? Lucy. Lucy.

– [The older boy stands up, moves away from the LEGO and picks up the 3DS] I’m not as into LEGO as I was…

– [The younger, still rummaging and sorting bricks] I need some sort of tray!

After twenty minutes or so of construction the structure illustrated on the box and in the instructions booklet is still far from complete. It is supposed to form a tall hoop-like shape, a ‘portal’ now familiar from SF and fantasy film and TV. Whilst the actual LEGO play has proved absorbing, particularly for the younger child, the lure of the videogame and its promise to connect with and animate the minifigs and vehicles is overwhelming. With a little pragmatic testing they determine that only the base of the portal is needed to connect the figures to the videogame. I plug the base into the console’s USB port and they quickly find the disc, load it into the Wii U. After patiently waiting for the console to download an update they watched the introductory cutscenes and conduct some initial exploration of the gameworld and control mechanism. They worked out quickly where and when the minifigs, on their RFID-enabled bases, needed to be placed on the platform to solve onscreen puzzles. This placing was done carelessly and quickly, eyes on the screen.

– Yay! We’ve done it!

– [With exaggerated American accent] Oh my gaad, so exc-iting!

[After the first puzzle is solved, the older boy guides the younger:]

– Press A

– Where’s Batman? Let me try.

– It’s working – it’s working – it’s working

– Go through there…

– The speed!!

Observing this play over several hours it became apparent that the navigation of space was less significant to the structure of the play and the behaviours of the human and nonhuman players than was the negotiation of time. The LEGO Dimensions game sets both absolute and negotiable constraints on the temporal and attentional dimensions of play, for example it mirrors the traditional construction of LEGO – the relative slowness and rhythm of checking printed instructions, rummaging for the required brick, clicking it into place – on the screen with a virtual booklet that can be flicked through at speed, the software automatically completing the virtual version of the model. The younger child’s love of actual LEGO construction fought with the screen’s insistent promise of animated action. Some animated cutscenes and tutorials can be skipped, others can’t, an automated disciplining of attention. Rhythm and speed are impelled and constrained by machinic cape-abilities… scrutinising diagrams, finding the necessary piece in actual play, by the coded rhythm of the videogame – and the affordances of the avatars. Videogames set puzzles to slow progression through their levels, and to play a new game is to learn the puzzle of the game itself – what does it need the player to do to progress (Giddings & Kennedy 2008)? And gameplay takes on a markedly different rhythm and attention once players are familiar with its machinic demands, but at the same time different speeds and competences are driven by the different ages of the children, generating a dynamic that flows between supportive instruction and tetchy impatience and frustration. From the split-second button-press to swap an avatar or flick a switch, to the minutes or hours to complete the actual portal, the days needed to play through the game to the month- or year-long duration of movie and game sequel releases (in the cinema, then on DVD or streaming services), the collection of new figures and sets to expand this starter set, punctuated by birthdays and Christmas.

This particular moment of play, for all the novelty of the new game sets (‘we’re the first people to play this!’ they whispered at one point), is also part of at once the longitudinal flows of both domestic media life and entertainment-industrial strategy. Immediate recognition of the Lucy / Wyldstyle character, the Batman joke about only working ‘in black, and sometimes very very dark grey’, the repeated refrains from the song ‘Everything is Awesome’ demonstrate the boys were very familiar with the LEGO Movie as well as the toys, and so cued in to its specific iterations of characters and mode of humour, as well as the diffuse and ubiquitous popular media universe it brings to bear (Batman, Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter). As Meredith Bak notes, whereas Disney had to work hard to equalise and blend its distinct storyworlds to ‘create a modular system’ for the Infinity system, LEGO has always been modular and its distinctive studs and standardised minifigs easily dissolve proprietory IP into its recent fantastical products and ‘an infinitely compatible, sanctioned multiverse’ (Bak 2016: 59). Thus in the opening sequences of the game the players encounter Batman rescuing Gandalf from the Balrog, but then two versions of Batman (one moulded from light grey virtual thermoplastic, the other black) fight it out for authenticity.

In the tiny moment of constructive play described above, the Batman character is heralded by his self-parodic description from the LEGO Movie, but also, for parents watching or playing along, he is doubled to evoke memories of the various iterations of screen Batman from the camp 1960s TV series to the recent, darker, films. The confusion of the Dumbledore / Gandalf character hints at the limits of this semiotic strategy (itself a legacy of earlier cultural-industrial semiotic strategies of the trademark (Gaines 1991)). Each wizard in its own cinematic representation is too closely constituted by generic signifiers of wizardness – long grey beard, robes, staff, extravagant hat – and as such prove non-toyetic (in the conventional sense of the word). For all their intended semiotic chaos, the LEGO Dimensions and LEGO Movie worlds are syncretic but not homogenous – IP edges are carefully fenced with (r) and ™ symbols and elaborate industrial arrangements for licensing across Marvel, Disney, Warner Bros, etc. etc. So whilst the toyetic aesthetic nearly always reinforces commercial transmedia generic zoning (Harry Potter’s glasses and scar, the distinct colours and logos of superheroes and Monsters Inc.), Gandalf/Dumbledore represents a lapse in toyetic attention – a momentary industrial-transmedial failure.

[Black-clad Batman runs to and fro in a LEGO forest, collecting gold and silver studs. Even in the mini-Batmobile he can’t get past an agressive tree blocking the path. Control is switched to Wyldstyle but she is immediately overwhelmed an attack from a troop of flying monkeys from The Wizard of Oz. Gandalf does not appear to be an option on this level]

– [Quietly] There’s no Dumbledore, we can’t do it…

[…]

– Where’s Dumbledore? Dumbledore is no more.